British foreign policy in the Middle East has involved multiple considerations, particularly over the last two and a half centuries. These included maintaining access to British India, blocking Russian or French threats to that access, protecting the Suez Canal, supporting the declining Ottoman Empire against Russian threats, guaranteeing an oil supply after 1900 from Middle East fields, protecting Egypt and other possessions in the Middle East, and enforcing Britain's naval role in the Mediterranean. The timeframe of major concern stretches from the 1770s when the Russian Empire began to dominate the Black Sea, down to the Suez Crisis of the mid-20th century and involvement in the Iraq War in the early 21st. These policies are an integral part of the history of the foreign relations of the United Kingdom.

Napoleonic Wars (1793-1815)

[edit]Prior to 1798, English, Scottish and British interests after the end of the Crusader states of Outremer in the Near East was limited to commercial interests like the Elizabethan Levant Company, and tangential matters in foreign policy: for example, in 1737 Britain had attempted to negotiate with Russia over the fate of the fortresses of the Caucasus in a bid to secure Russian support for Britain's ally Austria in general European policy during their war of 1737–39 with the Ottomans.[1] The Royal Navy had been involved in policing the sea lanes to the Barbary Coast to prevent raids by Arab and Berber slavers on European and British shores (of which the peak was around 1625-27 when the raids extended into Cornwall and even as far north as Iceland), but these were limited by lack of suitable bases (Tangier fell to Morocco shortly after it's cession by Portugal to Britain, and Gibraltar from 1704 was limited).

Napoleon Bonaparte, the antagonist of the French wars against Britain from the late 1790s until 1815, used the French fleet to convey a large invasion army to Egypt, a major province of the Ottoman Empire. British commercial interests represented by the Levant Company had a successful base in Egypt, and indeed the company handled all Egypt's local diplomacy. The British Royal Navy under Admiral Horatio Nelson responded and sank the French fleet at the Battle of the Nile in 1798, thereby trapping Napoleon's army in Egypt.[2] Napoleon escaped. The army he left behind was decimated by disease and defeated by the British and Ottoman forces at the Battle of Acre in 1801 and the survivors returned to France. In 1807 when Britain was at war with the Ottomans, the British sent a further force to Alexandria, but it was defeated by the Egyptians under a local pasha who had seized power since 1805, Mohammed Ali and withdrew.

The Near East was a source of little concern for Great Britain after Napoleon's defeat in 1814-15, excepting attempted Russian penetration into Ottoman Turkey and Persia. Britain absorbed the Levant Company's services into the Foreign Office by 1825.[3][4]

Ottoman weakening (1815-53)

[edit]

Europe was generally peaceful from 1815, and the Greeks’ long war of independence was the major military conflict in the 1820s.[5] Serbia had gained its autonomy from Ottoman Empire in 1815. The Greek Revolution came next starting in 1821, with a rebellion indirectly sponsored by Russia. The Greeks had strong intellectual and business communities which employed propaganda echoing the French Revolution and contemporaneous Latin American revolutions that appealed to the popular romanticism of Western Europe. Despite harsh Ottoman reprisals like the Massacre of Chios in 1822, they kept their rebellion alive.

British policy of non-intervention reflected the opinion of the major architect of the Congress of Vienna peace, Klemens Wenzel von Metternich, Austria's prime minister from 1809 to 1848. At the Congress he had insisted on leaving Ottoman affairs outside the scope of the conference, and in fact he then sardonically asked if a British intervention in Greece gave the Austrian Empire the right to intervene in Ireland.[6] Public opinion was different, and sympathisers like Lord Byron played a major role in shaping British public opinion to strongly favor the Greeks, especially among romantics, Radicals, the Whig Opposition, and the Evangelicals.[7] However, the top British foreign policy makers George Canning (whose brother Stratford Canning later became ambassador to Constantinople) and Viscount Castlereagh were much more cautious. British policy down to 1914 was to preserve the declining Ottoman Empire, especially against hostile pressures from Russia. However, when Ottoman behavior was outrageously oppressive against Christians, London demanded reforms and concessions.[8][9][10]

The context of the three Great Powers' intervention was Russia's long-running expansion at the expense of the decaying Ottoman Empire. However, Russia's ambitions in the region were seen as a major geostrategic threat by the other European powers. Austria feared the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire would destabilize its southern borders. Russia's Tsar Alexander I, a big proponent of Orthodox mysticism, gave strong emotional support for the fellow Orthodox Christian Greeks. The French too were motivated by strong public support for the Greeks. The government in London paid special attention to the powerful role of the Royal Navy throughout the entire Mediterranean region, where Britain had gained Malta and the Ionian Islands as protectorates during the Napoleonic Wars. First limited to loans from banks negotiated by unaccredited, unofficial Greek diplomats in 1823, British action expanded fearing unilateral Russian action after Tsar Nicholas I acceding to the throne in support of the Greeks. Britain and France bound Russia by treaty to a joint intervention which aimed to secure Greek autonomy whilst preserving Ottoman territorial integrity as a check on Russia.[11]

The Powers agreed, by the Treaty of London (1827), to force the Ottoman government to grant the Greeks autonomy within the empire and despatched naval squadrons to Greece to enforce their policy.[12] The decisive Allied naval victory at the Battle of Navarino broke the military power of the Ottomans and their Egyptian allies. Victory saved the fledgling Greek Republic from collapse- from 1825 the force led by Mohammed Ali of Egypt's son on behalf of Ottoman sultan Mahmud II had been on the verge of victory against the Greeks. But it required two more military interventions, by Russia in the form of the Russo-Turkish War of 1828–29 and by a French expeditionary force to the Peloponnese to force the withdrawal of Ottoman forces from central and southern Greece and to finally secure Greek independence.[13] Greek nationalists proclaimed a new "Great Idea" whereby the little nation of 800,000 would expand to include all the millions of Greek Orthodox believers in the region now under Ottoman control, with Constantinople to be reclaimed as its capital. This idea was the antithesis of the British goal of maintaining the Ottoman Empire, and London switched from support to systematically oppose the Greeks in the further expansion of the new nation-state as delineated in suitably conservative boundaries in 1832, which comprised only Attica, the Cyclades and the Peloponnese.[14]

This would form a template for a British management of the Ottoman Empire's decline at the expense of Russia. The Russians reacted with renewed vigour in their dealings with the Ottoman Empire, attempting to bully their way into domination by pretexts of safeguarding the rights of Orthodox minorities in cases of diplomatic strongarming like the Treaty of Humkar Iselski in 1833. Similar moves had been made in the Caucasus when the Kingdom of Georgia had requested Russian protection in 1801, and on Persia following the Russian victories in the Russo-Persian Wars of 1813 and 1828, when the Treaty of Turkmenchay pushed Persia's borders beyond most of Azerbaijan, to where they are today. This built up a framework of Anglo-Russian competition for favour and influence amongst the polities of the Near East and Central Asia, dubbed the Great Game by Rudyard Kipling, that was to last into the 20th century.

It then alarmed the British to see the Egyptian pasha Muhammad Ali, whose influence had been growing since 1805 when he had effectively waged wars on behalf of the comparatively inactive Ottoman court of Constantinople in the Hejaz (against a Saudi and Wahabbist rebellion) and Greece, attempt to claim the mantle of Sultan for himself as he marched on Constantinople through Syria in the late 1830s, in outright rebellion against the Ottomans. Fearing the loss of their interests under a new rejuvenated ruler of the Ottoman Empire, a Quadruple Alliance of Great Britain, Austria, Prussia and Russia intervened on behalf of the new Ottoman sultan Abdulmecid I in 1839-40, defeating Mohammed Ali's forces sufficiently to force him to accept a compromise that allowed him and his successors hereditary rule of a viceroyalty (khediviate) of the Ottoman Empire based in Egypt that was only de jure under Ottoman rule. France under the July Monarchy had recently conquered the Ottoman vassal of the Beylik of Algiers, and therefore backed Mohammed Ali, was thus forestalled a second time in her devious designs on Egypt when the French government backed down from its promises of military help to Egypt. The compromise with Mohammed Ali proved lasting, and with his death in 1849 the khediviate passed to his son, beginning a dynasty that ruled until 1952.

Revolutions in Diplomacy (1853-78)

[edit]The Crimean War was a major conflict fought primarily in the Crimean Peninsula.[15] The Russian Empire lost to an alliance made up of Great Britain, France, Sardinia-Piedmont, and the Ottoman Empire.[16] The immediate causes of the war were minor, being the Russians’ intervention to uphold their rights to protect Orthodox Christians under the Treaty of Kucuyk Kaynarca, then considered to have been violated by a new agreement concluded with Napoleon III and his new regime over the rights of all Christians. The longer-term causes involved the decline of the Ottoman Empire and the spark of war with Britain was Russia's misunderstanding of the British position. Tsar Nicholas I visited London in person and consulted with Foreign Secretary Lord Aberdeen regarding what would happen if the Ottoman Empire collapsed and had to be split up. The tsar misread Britain's position as supporting Russian aggression, while London actually sided with Napoleon III and his new treaty, against any breakup of the Ottoman Empire and Russian expansion. When Aberdeen became Prime Minister in 1852, the tsar mistakenly believed he had British approval for action against Turkey and was shocked when Britain declared war in 1854 after a moderately successful action against Turkey in the Danubian Provinces. Despite Aberdeen's opposition to the war, and Austria stepping in to contain the war by demanding Russian withdrawal from the Danubian Provinces, public opinion demanded it, leading to his resignation and a war which could have been prevented from further escalation.[17] The new prime minister was jingoistic interventionist Lord Palmerston who strongly opposed Russia, and had touted British might liberally in the Near East like in the Don Pacifico affair. He defined the popular imagination which saw the war against Russia is a commitment to British principles, notably the defense of liberty, civilization, free trade; and championing the underdog. The fighting was largely limited to actions in the Crimean Peninsula and the Black Sea. Both sides badly mishandled operations; the world was aghast at the extremely high death rates due to disease. In the end, the Allied coalition prevailed with the Fall of Sevastopol, and Russia lost control of the Black Sea in the Treaty of Paris Russia in 1870 unilaterally repudiated this treaty and regained control of the Black Sea, leading to popular disillusionment about interventionism.[18][19][20]

Pompous aristocracy was a loser in the war, the winners were the ideals of middle-class efficiency, progress, and peaceful reconciliation. The war's great hero was Florence Nightingale, the nurse who brought scientific management and expertise to heal the horrible sufferings of the tens of thousands of sick and dying British soldiers.[21] according to historian R. B. McCallum the Crimean War:

- remained as a classic example, a perfect demonstration-peace, of how governments may plunge into war, how strong ambassadors may mislead weak prime ministers, how the public may be worked up into a facile fury, and how the achievements of the war may crumble to nothing. The Bright-Cobden criticism of the war was remembered and to a large extent accepted. Isolation from European entanglements seemed more than ever desirable.[22]

After the war, Russian ambitions had been curbed in the Near East for a while but the policy of controlling the rate of the Ottoman Empire's decline continued, and Britain intervened in 1860 to support the Druze in a civil war on Mount Lebanon, where a special administrative region (a mutasarrifate) so as to avoid being outmanoeuvred by the Russians and French, both of whom had religious minorities of Christians (Orthodox and Catholic or Unitate respectively) with long historical influence in the region, whereas Protestant missionaries were generally of little diplomatic worth. The Indian Mutiny of 1857 did little to shake British influence in the region, having recently dispatched expeditions to Persia in 1856 and Muscat and Oman to mediate disputes to British advantage. However, an attempt was had by the French to extend influence in the Khedive's dominion when his childhood friend Ferdinand de Lesseps was granted the permission to build the Suez Canal. It was to great dismay that the Canal was received by Palmerston, who feared the British control of the Cape of Good Hope route to the Orient would be neutralised, and that on the opening day of the Canal in 1869, the French imperial yacht was the first to cross it- but even more so for the French when in 1875, the bankrupt Khedive sold his part of the shares in the Suez Canal Company to the British government of Benjamin Disraeli, whose farsighted appreciation of the Canal's importance ensured a British majority shareholding in the Company. This ended yet another grasping French attempt on Egyptian sovereignty.

Worse was to come for the Ottomans, who were themselves first submerged by the Sultan's extravagant spending, and then in 1876 by a palace coup that put a reactionary clique under Abdul Hamid II on the throne after deposing his brother and a constitution, Turkey's first. The Russians took advantage of the chaos to insist on their rights of protection of Christians in the Balkans (Herzegovina and Bulgaria particularly) from being savaged by Turkish Muslim forces quelling an uprising. In 1877 Russia declared war and advanced rapidly, to the point that the other Great Powers, headed by the chancellor Otto von Bismarck of the newly unified German Empire proposed a conference that would redistribute the war spoils. The Berlin Conference (1878) ensured the creation of a Bulgarian state, which quickly became more and more Russified than the Treaty of Berlin allowed, enraging the Turkish delegation, who had ceded Cyprus to British military occupation as a bribe to support them. In addition austria-Hungary was permitted to occupy Bosnia and Herzegovina indefinitely as well, leading to an overall loss for the Ottomans. Disraeli's minister of foreign affairs, Lord Salisbury had seen it wise to not pursue escalation with Russia despite popular jingoism (“We don't want war but by jingo if we’ve got to/We‘ve got the ships, we‘ve got the men, we‘ve got the money too.“), but this enraged Liberal Opposition leader William Ewart Gladstone, who committed himself to a campaign against the “Jew” Disraeli's supposed complicity in the “Bulgarian massacres”, and won an electoral victory in 1880, setting the tone of British moralism in foreign policy.

Scramble for Africa (1878-1905)

[edit]As shareholders of the Suez Canal Company, both British and French governments had strong interests in the stability of Egypt. Most of the traffic was by British merchant ships. However, in 1881 the ʻUrabi revolt broke out, a nationalist movement led by colonel Ahmed ʻUrabi that murders European civilians and was against the administration of Khedive Tewfik, who collaborated closely with the British and French. Combined with the complete turmoil in Egyptian finances, the threat to the Suez Canal, and embarrassment to British prestige if it could not handle a revolt, London found the situation intolerable and decided to end it by force.[23] The French, however, were paralysed by an inconvenient cabinet crisis and did not join in. On 11 July 1882, Prime Minister William E. Gladstone ordered the bombardment of Alexandria which launched the short decisive Anglo-Egyptian War of 1882.[24][25] Egypt nominally remained under the sovereignty of the Ottoman Empire despite British occupation, and the Khedive's regime still ruled, and France and other nations had representation, but the British consul made the decisions. The Khedive (Viceroy) had been an Ottoman official but in practice, he operated under the close supervision of the British consul general. The dominant personality was Consul Evelyn Baring, 1st Earl of Cromer. He was thoroughly familiar with the British Raj in India, and applied similar policies to take full control of the Egyptian economy. London repeatedly promised to depart in a few years, but various pretexts kept the occupation in place until 1922.[26][27]

Historian A.J.P. Taylor says that the seizure of Egypt "was a great event; indeed, the only real event in international relations between the Battle of Sedan and the defeat of Russia in the Russo-Japanese war."[28] Taylor emphasizes long-term impact:

The British occupation of Egypt altered the balance of power. It not only gave the British security for their route to India, it made them masters of the Eastern Mediterranean and the Middle East. It made it unnecessary for them to stand in the front line against Russia at the Straits....And thus prepared the way for the Franco-Russian Alliance ten years later.[29]

Gladstone and the Liberals had a reputation for strong opposition to imperialism, so historians have long debated the explanation for this reversal of policy. The most influential was a study by John Robinson and Ronald Gallagher, Africa and the Victorians (1961). They focused on The Imperialism of Free Trade and promoted the highly influential Cambridge School of historiography. They argue that the Liberals had no long-term plan for imperialism but acted out of necessity to protect the Suez Canal amid a nationalist revolt and the threat to law and order in Egypt. Gladstone's decision was influenced by strained relations with France and the actions of British officials in Egypt. Critics like Cain and Hopkins emphasize the need to protect British financial investments in Egypt, downplaying the risks to the Suez Canal. Unlike Marxists, they focus on "gentlemanly" financial interests rather than industrial capitalism.[30]

A.G. Hopkins rejected Robinson and Gallagher's argument, citing original documents to claim that there was no perceived danger to the Suez Canal from the ‘Urabi movement, and that ‘Urabi and his forces were not chaotic "anarchists", but rather maintained law and order.[31] : 373–374 He argues that Gladstone's cabinet was motivated by the need to protect British bondholders' investments in Egypt and to gain domestic political popularity. Hopkins points to the significant growth of British investments in Egypt, driven by the Khedive's debt from the Suez Canal's construction, and the close ties between the British government and the economic sector.[31]: 379–380 He writes that Britain's economic interests occurred simultaneously with a desire within one element of the ruling Liberal Party for a militant foreign policy in order to gain the domestic political popularity that enabled it to compete with the Conservative Party.[31]: 382 Hopkins cites a letter from Edward Malet, the British consul general in Egypt at the time, to a member of the Gladstone Cabinet offering his congratulations on the invasion: "You have fought the battle of all Christendom and history will acknowledge it. May I also venture to say that it has given the Liberal Party a new lease of popularity and power."[31]: 385 However, Dan Halvorson argues that the protection of the Suez Canal and British financial and trade interests were secondary and derivative. Instead, the primary motivation was the vindication of British prestige in both Europe and especially in India by suppressing the threat to "civilised" order posed by the Urabist revolt.[32][33]

Nevertheless, British influence in Egypt only strengthened much to Gladstone's dismay. As an anti-imperialist skeptic, his search for pretexts to leave Egypt came to naught, and ultimately Liberal and Conservative colonial policy did not differ over the next six decades- excepting that the Liberals’ dithering over intervention to assist war hero General Charles Gordon at Khartoum in 1885, where he had been fighting the Mahdist rebellion on behalf of the Khedive's colonial project in the Sudan (conquered by Mohammed Ali in the 1820s for his Egyptian realm) which led arguably to the fall of Gladstone. The Conservatives, now under Salisbury, participated enthusiastically in the Scramble for Africa, formally declaring British protectorates after concluding protection treaties with the native authorities of British Somaliland, the Sultanate of Zanzibar, and Oman. The abolitionism of slavery from the Indian Ocean Arab slave trade and white slavery (sexual trafficking in modern terminology) was a key ethical component of the Powers’ otherwise self/awarded mandate to dividing Africa into spheres of influence, and to that end British consuls in Tripoli and Zanzibar were particularly stringent, sheltering runaways and buying and freeing slaves with their own money.[34]

By the turn of the century the war against the Mahdi (who had emerged after the British occupation) and his fanaticism in the Sudan had mostly drawn to a close, with the remains being defeated at the Battle of Omdurman in 1898, under General Herbert Kitchener, who diplomatically defended the Anglo-Egyptian Condominium over Sudan from the encroachment of France, who backed down after the Fashoda Crisis of 1898. French encroachment on Egypt would have to wait until the emergence of a mutual antagonism to Wilhelm II and Weltpolitik Germany, and therefore the conclusion of the Entente Cordiale in 1904, dividing the conflicting zones of influence and ending a dogged French diplomatic harassment of British consul's activity in Egypt at last.[35] It was largely noted by the French ministers Théophile Délcassé and Paul Cambon that Britain was a power that shared interests in colonial affairs, and they therefore received overtures of peace from Edward VII and ministers like Salisbury well.

Anglo-German confrontation (1905-14)

[edit]The Ottoman Empire leadership had been hostile to its traditionally loyal Armenian millet, third in the classical Ottoman Empire after Muslims and Greeks, and in the run up to World War I accused it of favouring Russia. The result was an attempt to relocate and ethnically cleanse Armenians, in which hundreds of thousands died in the Armenian genocide.[36] Since the late 1870s Gladstone had moved Britain into playing a leading role in denouncing the harsh policies and atrocities and mobilizing world opinion. In 1878–1883 Germany followed the lead of Britain in adopting an Eastern policy that demanded reforms in the Ottoman policies that would ameliorate the position of the Armenian minority.[37] However this did not stop a shift towards violence starting in 1895 in the Ottoman Empire, and causing emigration.

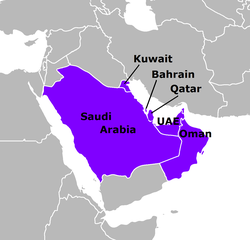

Germany saw the Ottoman Enpire as a suitable target for expansionism, though not in the manner of Africa; instead the oilfields of the Persian Gulf, discovered in 1908, made control of the region paramount for any industrial world power. The Power with the most interests in the area has been Britain, with protectorates over the Trucial States, Kuwait and Aden. The Berlin-Baghdad railway project was viewed with suspicion by the British, who rapidly formed an Anglo-Persian Oil Company and secured a monopoly from the Qajar Shah Mohammmad Ali of Persia to the rights in the region. Russia too was conciles given the newfound importance of Persia- a state run by financially deplorable extravagance under the Qajar dynasty, which had had its attempts at constitutional reform frustrated since the 1850s. In 1905 a moderately successful Persian Constitutionalist Revolution succeeded with the backing of the British consulate, but the conclusion of the Anglo-Russian Entente in 1907 dividing Persia into zones of influence left Russia a blank cheque to intervene when the more anti-constitutional Shah Mohammed Ali ascended. Britain now stayed out of the affair, loathe to sacrifice diplomatic agreement for the Constitutionalists. In Rgypt too local nationalist sentiments reared its head as Egyptians chafed under perceived racial slights like the 1906 Denshawai incident. Pan-Islamism and Pan-Arabism both had their intellectual and political roots in Egypt under British rule, providing the most tolerant press freedom in any Arab country at the time.

The Young Turks clique also forced a similar regime change despite British support for the Ottomans. In 1909 the old Abdul Hamid II had been forced out after the annexation of Bosnia by Austria the previous year and Bulgarian unilateral Declaration of Independence, and was replaced by his brother Mehmed V. The new government shifted radically (more so than under Abdul Hamid II) away from multiethnic imperialism to nationalist ethnic state, and were happy to play the Germans off the British and Russians. In 1913 they came to form a Unionist dictatorship in a coup after the defeat of Turkey by her former vassals Serbia, Montenegro, Greece and Bulgaria in the First Balkan War, and was forced to cede all of Rumelia except Constantinople. The new regime was headed by militarists Enver Pasha, naval minister Jamal Pasha and Tewfik Pasha, whose pro-German stance was undisguised, and they participated in the Second Balkan War, retaking Thrace. In October 1914 Enver Pasha would conspire to have the SMS Goeben and SMS Breslau, German warships gifted to Turkey, attack Russia before Turkey joined the war, forcing Russia to declare a War where much of the Turkish population had hoped to stay neutral and profit from.

Persian Gulf

[edit]

In 1650, British diplomats signed a treaty with the Sultan at Oman declaring that the bond between the two nations should be "unshook to the end of time."[38] British policy was to expand its presence in the Persian Gulf region, with a strong base in Oman. Two London-based companies were used, first the Levant Company and later the East India Company. The shock of Napoleon's 1798 expedition to Egypt led London to significantly strengthen its ties in the Arab states of the Persian Gulf, pushing out the French and Dutch rivals, and upgrading the East India Company operations to diplomatic status. The East India Company also expanded relations with other sultanates in the region, and expanded operations into southern Persia. There was something of a standoff with Russian interests, which were active in northern Persia.[39] The commercial agreements allowed for British control of mineral resources, but the first oil was discovered in the region in Persia in 1908. The Anglo-Persian Oil Company activated the concession and quickly became the Royal Navy's main source of fuel for the new diesel engines that were replacing coal-burning steam engines. The company merged into BP (British Petroleum). The main advantage of oil was that a warship could easily carry fuel for long voyages without having to make repeated stops at coaling stations.[40][41][42]

Aden

[edit]When Napoleon threatened Egypt in 1798, one of his threats was to cut off British access to India. In response the East India Company (EIC) negotiated an agreement with Aden's sultan that provided rights to the deepwater harbor on Arabia's southern coast including a strategically important coaling station. The EIC took full control in 1839. With the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, Aden took a much greater strategic an economic importance. To protect against threats from the Ottoman Empire, the EIC negotiated agreements with sheikhs in the hinterland, and by 1900 had absorbed their territory. Local demands for independence led in 1937 to designation of Aden as a Crown Colony separate from India.[43] Nearby areas were consolidated as the Western Aden protectorate and Eastern Aden protectorate. Some 1300 sheikhs and chieftains signed agreements and remained in power locally. They resisted demands from leftist labor unions based in the ports and refineries, and strongly opposed the threat of Yemen to incorporate them.[44] London considered the military base and Aiden as essential to protect its oil interest in the Persian Gulf. Expenses mounted, budgets were cut, and London misinterpreted the mounting internal conflicts.[45] In 1963 the Federation of South Arabia was set up that merged the colony and 15 of the protectorates. Independence was announced, leading to the Aden Emergency--a civil war involving Soviet-backed National Liberation Front fighting the Egyptian-backed Front for the Liberation of Occupied South Yemen. In 1967 the Labour government under Harold Wilson withdrew its forces from Aden. The National Liberation Front quickly took power and announced the creation of a communist People's Republic of South Yemen, deposing the traditional leaders in the sheikhdoms and sultanates. It was merged with Yemen into People's Democratic Republic of Yemen, with close ties to Moscow.[46][47][48]

First World War (1914-36)

[edit]

World War I

[edit]The Ottoman Empire entered World War I on the side of Germany in October 1914 through a piece of chicanery by Enver Pasha, and immediately became an enemy of Britain and France. Four major Allied operations attacked the Ottoman holdings.[49] The Gallipoli Campaign to control the Dardanelles failed in 1915-1916, forcing First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill to resign. The first Mesopotamian campaign invading Iraq from India also failed at the Siege of Kut. The second one captured Baghdad in 1917. The Sinai and Palestine campaign from Egypt was a British success, defending the Suez Canal and advancing into Palestine with support on the flank from a British funded Arab Rebellion under Faisal I, second son of the Sharif of Mecca, whose legitimacy in Sunni Islam was sought to counter the Ottoman caliph's claims to raise jihad that were causing anti-colonial uprisings in Allied Muslim populations from the Volta to India. Colonel T.E. Lawrence (“of Arabia”) was instrumental in carrying out instructions and diplomacy of British High Commissioner (title created in 1914 when the Ottoman siding with the Central Powers had allowed the British to declare the Ottoman vassal, Khedivial Egypt independent as a Sultanate under British protection) Henry McMahon.

Throughout the First World War the British colonies in the Middle East (term created in 1902) were under considerable rebellious pressure: from the Senussi rebellion, in the Libyan Desert to the Dervish State in British Somaliland. The British Indian Army was deployed mostly to East Africa and Mesopotamia, with minimal involvement in Europe until Kitchener‘s Army of 100,000 could be trained.[50] Australian and New Zealand troops participated en masse in the Gallipoli and Palestine campaigns, where the Allies captured Jerusalem in December 1917 under the new general Edmund Allenby.

By 1918 the Ottoman Empire was a military failure, as Enver Pasha hid documents that cast the war in a bad light from the country and embarked on plans to conquer the Caucasus from the decaying Russian administration, which was supplanted by British intervention and occupation to ward off the Bolsheviks, of Azerbaijan and Armenia in mid-1918, stopping short of international recognition. Turkey signed an armistice in late October that amounted to surrender and permitted Allied occupation of Constantinople, the first since 1453.[51] However the Allied politicians and armies disagreed amongst themselves over the divisions of war: the British and French diplomats Sir Mark Sykes and François-Georges Picot agreeing to a preliminary postwar partition of the Middle East in 1916 had Ben leaked to an indignant Prince Faisal by the Bolsheviks after the October Revolution of 1917, and the growing Zionist movement of Chaim Weizmann applied pressure to David Lloyd George and foreign minister Arthur Balfour to declare in favour of a loosely defined “Jewish homeland” in Palestine. Perhaps imagining Jewish and Zionist influence in the United States and the Bolsheviks to be greater than it was, the Declaration was issued in November 1917 to galvanise sympathetic elements in both (to little effect). In any case, the principles of Woodrow Wilson of ethnic self-determination were not applied at the Paris Peace Conference, with the Powers dividing up the Middle East between themselves, and only superficially acknowledged Wilsonian goals by terming their new territories Mandates of the newly instated League of Nations rather than protectorates.

The only lasting sections of the post-1918 order were those settled not at the negotiating table but by force. In Anatolia Mustafa Kemal challenged the Treaty of Sèvres that was signed by the Sultan's government with the occupying powers in 1920, repudiating both the Sultanate and the Treaty, and forcing recognition of his government after military defeat of Britain and her ally Greece, who had been encouraged to attack ever deeper into Anatolia even as Lloyd George's policy antagonised the Italians and French, who gave up their own claims to Anatolia, and then at the Chanak Crisis of 1922, the British Dominions as well, who refused to be committed to a fight against their consent so quickly after Gallipoli. The fall of Lloyd George meant the return of the Conservatives, who looked more kindly upon Kemal and invited him to London in February 1923 to sign the revised peace with the Sultan's government also in situ, the Treaty of Lausanne. The Caucasian states’ fate was also decided by arms as after British withdrawal in 1920, faced by budget cuts and demand to demobilise, the Allies gradually withdrew from the Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War, and the Bolsheviks invaded and set up puppet Soviet Republics in the former Russian imperial territories.

Persia too was faced with political instability, despite having been neutral- both sides had freely violated Persian sovereign borders during the war, the Germans going as far as to send the Niedermayer-Hentig expedition to try to raise rebellion in British India and the British protected Emirate of Afghanistan through Persia. Despite Anglo-Russian occupation, the Bolshevik Revolution caused a power vacuum in northern Persia, and the prime minister, Reza Pahlavi, was later backed by the British into seizing power and became Shah in 1925, founding the Pahlavi dynasty.

Partition of Ottoman Empire

[edit]The other postwar settlement in the Middle East, the partition of the non-Turkish parts of the Ottoman Empire (30 October 1918 – 1 November 1922) was a geopolitical event that was also determined by force rather than by diplomacy, that occurred after World War I and the occupation of Istanbul by British, French, and Italian troops in November 1918. The partitioning was planned in several agreements made by the Allied Powers early in the course of World War I,[52] notably the Sykes–Picot Agreement, after the Ottoman Empire had joined Germany to form the Ottoman–German Alliance.[53] The huge conglomeration of territories and peoples that formerly comprised the Ottoman Empire was divided into several new states. They included Palestine, an international area, Mesopotamia under British suzerainty, and Greater Syria, Greater Lebanon, and Kurdistan under French suzerainty.[54] This reflects the prewar ambitions of the French in Syria, but conflicted with an uncommitted deal made to Faisal bin Hussein, son of the Sharif of Mecca, whose disloyalty to the Ottomans had seen him accompany Allenby's army as it's right flank from Sinai to Damascus in October 1918. The Greater Syria that a council of Arab leaders set up was unrecognised by the Allies at Versailles, and invaded by French troops under General Henri Gouraud in 1919. Faisal was forced to flee to Jerusalem, where he was made the head of a new Iraqi mandate as compensation, and his brother Abdullah I that of Transjordan, separated from Palestine in 1920.

The Ottoman Empire had been the leading Islamic state in geopolitical, cultural and ideological terms. The dismantling of the Caliphate by Kemalist Turkey led to the anguished death rattles of the pro-Caliph Khalifata movement that had sprung up in the wave of rebellion across colonial territories after the First World War, many of which are appeased by the British for lack of more suitable dealing, with Egypt under the Wafd patriots becoming de jure independent in 1922 when the protectorate was terminated, albeit with British control of the Suez Canal. The partitioning of the Ottoman Empire after the war led to the domination of the Middle East by Western powers such as Britain and France, and saw the creation of the modern Arab world and the Republic of Turkey. Resistance to the influence of these powers came from the Turkish National Movement but did not become widespread in the other post-Ottoman states until the period of rapid decolonisation after World War II. The League of Nations mandate granted after the Allies cleared up their conflicting claims at the San Remo Conference in 1920, the French Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon, the British Mandate for Mesopotamia (later Iraq) and the British Mandate for Palestine, later divided into Mandatory Palestine and the Emirate of Transjordan (1921–1946). The Ottoman Empire's possessions in the Arabian Peninsula became the Kingdom of Hejaz, which the Sultanate of Nejd (today Saudi Arabia) was allowed to annex by the British following the Hashemites’ falling out of favour with them between 1918 and 1922, and the Mutawakkilite Kingdom of Yemen became an independent state under British suzerainty. The Ottoman Empire's possessions on the western shores of the Persian Gulf were variously annexed by Saudi Arabia (al-Ahsa and Qatif), or remained British protectorates (Kuwait, Bahrain, and Qatar) and became the Arab States of the Persian Gulf.

In the 1920s, British policymakers debated two alternative approaches to Middle Eastern issues. Many diplomats adopted the line of thought of T. E. Lawrence favoring Arab national ideals. They backed the Hashemite family for top leadership positions. The other approach led by Arnold Wilson, the civil commissioner for Iraq, reflected the views of the India office. They argue that direct British rule was essential, and the Hashemite family was too supportive of policies that would interfere with British interests. The decision was to support Arab nationalism, sidetracked Wilson, and consolidate power in the Colonial Office. [55][56][57]

Mandates for Mesopotamia and Iraq

[edit]The British seized Baghdad in March 1917. In 1918 it was joined to Mosul and Basra in the new nation of Iraq as a League of Nations Mandate. Experts from India designed the new system, which favoured direct rule by British appointees, and demonstrated distrust of the aptitude of local Arabs for self-government. The old Ottoman laws were discarded and replaced by new codes for civil and criminal law, based on Indian practice. The Indian rupee became the currency. The army and police were staffed with Indians who had proven their loyalty to the British Raj.[58] Mosul had been allocated to France under the 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement and was subsequently given to Britain under the 1918 Clemenceau–Lloyd George Agreement. In 1921 at the Cairo Conference Winston Churchill made the decision to join the three Ottoman vilayets (provinces) of Mosul, Baghdad and Basra into the Kingdom of Iraq, despite their heterogenous majority-religious and ethnic compositions, given to Faisal to rule under a British mandate.

The large-scale Iraqi revolt of 1920 was crushed in the summer of 1920 but it was a major stimulus for Arab nationalism.[59] The Turkish Petroleum Company was given a monopoly on exploration and production in 1925. Important oil reserves were First discovered in 1927; the name was changed to the Iraq Petroleum Company (IPC) in 1929. It was owned by a consortium of British, French, Dutch and American oil companies, and operated by the British until it was nationalized in 1972.[60]

Great Britain and Turkey disputed control of the former Ottoman province of Mosul in the 1920s. Under the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne Mosul fell under the British Mandate of Mesopotamia, but the new Republic of Turkey claimed the province as part of its National Pact area. A three-person League of Nations committee went to the region in 1924 to study the case and in 1925 recommended the region remain connected to Iraq, and that the British should hold the mandate for another 25 years, to assure the autonomous rights of the Kurd population. Turkey rejected this decision. Nonetheless, Britain, Iraq and Turkey made a treaty on 5 June 1926, that mostly followed the decision of the League Council. Mosul stayed under British Mandate of Mesopotamia until Iraq was granted independence in 1932 by the urging of King Faisal, though the British retained military bases and transit rights for their forces in the country. Iraq was permitted to become an independent state de jure in 1932, but remained under British influence until the overthrow of the Hashemite monarchy in 1958.

Mandate for Palestine

[edit]

During the War, Britain produced three contrasting, but feasibly compatible, statements regarding their ambitions for Palestine. Britain had supported, through British intelligence officer T. E. Lawrence, the establishment of a united Arab state covering a large area of the Arab Middle East in exchange for Arab support of the British during the war. The Balfour Declaration of 1917 encouraged Jewish ambitions for a national home. Lastly, the British promised via the Hussein–McMahon Correspondence that the Hashemite family would have lordship over most land in the region in return for their support in the Arab Revolt. The Arab Revolt, which was in part orchestrated by Lawrence, had resulted in British forces under General Edmund Allenby defeating the Ottoman forces in 1917 in the Sinai and Palestine Campaign and occupying Palestine and Syria. The land was administered by the British for the remainder of the war. At the San Remo conference, Mandatory Palestine was placed under direct British administration rather than be given up despite Colonial Secretary Winston Churchill's opinion that it would be more trouble to keep,[61] and the Jewish immigrant population was allowed to increase, initially under the British High Commissioner and Anglo-Jewish Zionist Sir Herbert Samuel, former Postmaster General of the United Kingdom.

Already in 1920 there were conflicts between the Jewish agricultural settlers who remained mostly segregated with Arab peasantry, and disputes over water rights led to Jewish brigades like that of Igor Jabotinsky forming, and violent incidents like the Nebi Musa riots. Throughout the period of Mandatory Palestine the British exercised a generally favourable policy to the Zionists, according to Tom Segev, allowing the Zionist project to flourish. In 1923 Britain transferred a part of the Golan Heights to the French Mandate of Syria, in exchange for the Metula region. The continuation of unrest from Jewish settlements led in 1929 to Jaffa riots that provoked a White Paper in 1930 authored by the Labour Government Colonial Secretary Lord Passfield, that argued in favour of halting immigration but Chaim Weizmann used his influence with the Conservatives who entered into a National Government the next year, to have a Zionist High Commissioner, Sir Arthur Wauchope appointed.[62] Not only did immigration go up threefold (the Jewish population increased from 174,606 to 329,358), but Jews also increased their land holdings (in 1931 they increased their land holdings by 18,585 dunams or 4,646 acres, while in 1935 they increased them by 72,905), and finally Jewish business and commerce enjoyed an economic boom.[63] The rate of Jewish migration increased and along with it dissatisfied Arab Palestinians, whose Arab Revolt began in 1936 following the martyrdom of a Palestinian at the hands of Jewish settlers the year before.

The Second World War (1936-48)

[edit]After the Arab Revolt was suppressed the 1939 St James Round Table Conference was called on the basis of the Peel Commission findings in 1937, recommending a halt to immigration but denying Britain had right to partition the land. A 1939 White Paper now sought to divide Palestine into Jewish and Arab states, which was not accepted by either delegation. The beginning of World War Two in September delayed any further proposal. The Middle East remained in British hand's throughout the war, though with some moments of weakness: in June 1940 the Fall of France left Axis bases in Vichy French controlled Syria and Lebanon in range of British oilfields in Iraq, and a campaign was mounted to occupy these territories, which were granted independence in 1943 de jure and 1945-46 de facto by Britain without consulting Charles de Gaulle and Free France. The occupation of Iran was also necessary in 1941 from a military point of view, and was done so after Operation Barbarossa made the USSR a British ally, the two splitting Iran into zones of occupation to ensure a flow of raw materials into the USSR and for the good behaviour of Mohammed Reza Pahlavi, brought in to replace his pro-German father in 1941.

The Anglo-Iraqi War (2–31 May 1941) was a British military campaign to regain control of Iraq and its major oil fields.[64] Rashid Ali had seized power in 1941 with assistance from Germany. The campaign resulted in the downfall of Ali's government, the re-occupation of Iraq by the British, and the return to power of the Regent of Iraq, Prince Abd al-Ilah, a British ally.[65][66] The British launched a large pro-democracy propaganda campaign in Iraq from 1941 to 1945. It promoted the Brotherhood of Freedom to instil civic pride in disaffected Iraqi youth. The rhetoric demanded internal political reform and warned against growing communist influence. Heavy use was made of the Churchill-Roosevelt Atlantic Charter. However, leftist groups adapted the same rhetoric to demand British withdrawal. Pro-Nazi propaganda was suppressed. The heated combination of democracy propaganda, Iraqi reform movements, and growing demands for British withdrawal and political reform became as a catalyst for postwar political change.[67][68]

After the entry of the United States into the war, the Axis drive across North Africa by Erwin Rommel and the Afrika Korps was halted by the British at El Alamein, chasing the Axis to Tunisia where Anglo-American landings in Operation Torch seized the Vichy North African possessions of French Morocco, French Algeria and French Tunisia, which defected almost without a struggle to the side they saw winning the war. Tunisia fell in May 1943, and te invasion of Sicily toppled Mussolini in July 1943, forcing Germany to invade after a peace was signed with the Allies. Britain occupied the former Italian East Africa and Italian Libya, administering them until 1952 and 1951 respectively with the help of the French and Ethiopians.

The end of the war in the Middle East saw the resumption of sectarian hostilities as Jewish and Arab brigades in the British Army were demobilised and began fighting again, this time the Jews rebelling against British halts to immigration since 1939 despite the Holocaust and its displaced. British ships detained the refugees on Cyprus, and the uprising led to he assassination of British Cairo Resident Lord Moyne, and the terrorist attack by the Irgun on the King David Hotel in 1946. With mounting opposition to the Palestinian question, the territory was turned over to a United Nations vote which partitioned the area into two states in July 1947. British departure for June 1948 meant that military equipment was often given to Jewish militias in lieu of suitable Palestinian counterparts, and the drawing up of battle lines was completed well before the termination of British rule on the 30th of June, and the Arab armies of Syria, Iraq, Egypt, Jordan, and Lebanon converged on the newly declared Israel.

In 1955, the United Kingdom was part of the Baghdad Pact with Iraq. King Faisal II of Iraq paid a state visit to Britain in July 1956.[69] The British had a plan to use 'modernisation' and economic growth to solve Iraq's endemic problems of social and political unrest. The idea was that increased wealth through Oil production would ultimately trickle down to all elements and thereby thus stave off the danger of revolution. The oil was produced but the wealth never reached below the elite. Iraq's political-economic system put unscrupulous politicians and wealthy landowners at the apex of power. The remained in control using an all-permeating patronage system. As a consequence very little of the vast wealth was dispersed to the people, and unrest continue to grow.[70] In 1958, monarch and politicians were swept away in a vicious nationalist army revolt.

Suez Crisis of 1956

[edit]The Suez Crisis of 1956 was a major disaster for British (and French) foreign policy and left Britain a minor player in the Middle East because of very strong opposition from the United States. The key move was an invasion of Egypt in late 1956 first by Israel, then by Britain and France. The aims were to regain Western control of the Suez Canal and to remove Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser, who had just nationalised the canal. After the fighting had started, intense political pressure and economic threats from the United States, plus criticism from the Soviet Union and the United Nations forced a withdrawal by the three invaders. The episode humiliated the United Kingdom and France and strengthened Nasser. The Egyptian forces were defeated, but they did block the canal to all shipping. The three allies had attained a number of their military objectives, but the canal was useless. U.S. president Dwight D. Eisenhower had strongly warned Britain not to invade; he threatened serious damage to the British financial system by selling the US government's pound sterling bonds. The Suez Canal was closed from October 1956 until March 1957, causing great expense to British shipping interests. Historians conclude the crisis "signified the end of Great Britain's role as one of the world's major powers".[71][72][73]

East of Suez

[edit]After 1956, the well-used rhetoric of the British role East of Suez was less and less meaningful. The independence of India, Malaya, Burma and other smaller possessions meant London had little role, and few military or economic assets to back it up. Hong Kong was growing in importance but it did not need military force. Labour was in power but both parties agreed on the need to cut the defence budget and redirect attention to Europe and NATO, so the forces were cut east of Suez. [74][75][76]

See also

[edit]- History of the Middle East

- Russia–United Kingdom relations

- Egypt–United Kingdom relations

- France–United Kingdom relations

- Iran–United Kingdom relations

- Iraq–United Kingdom relations

- Israel–United Kingdom relations

- Foreign relations of the Ottoman Empire

- Turkey–United Kingdom relations

- International relations (1648–1814)

- Military history of the United Kingdom

- United States foreign policy in the Middle East

Notes

[edit]- ^ Simms, Brendan Three Victories and a Defeat

- ^ Piers Mackesy, British Victory in Egypt, 1801: The End of Napoleon's Conquest (1995).

- ^ M.S. Anderson, The Eastern Question: 1774-1923, (1966) pp 24-33, 39-40.

- ^ J.A.R. Marriott, The Eastern Question (1940) pp 165-83.

- ^ Macfie, pp 14-19; Anderson, pp 53-87.

- ^ Mazowrt, Mark The Greek Revolution

- ^ Robert Zegger, "Greek Independence and the London committee," History Today (1970) 20#4 pp 236-245.

- ^ Kenneth Bourne, The foreign Policy of Victorian England 1830-1902 (1970) p. 19.

- ^ Rich. Great Power Diplomacy: 1814–1914 (1992) pp. 44–57.

- ^ Allan Cunningham, "The philhellenes, Canning and Greek independence." Middle Eastern Studies 14.2 (1978): 151-181.

- ^ Henry Kissinger. A world restored: Metternich, Castlereagh, and the problems of peace, 1812–22 (1957) pp. 295–311.

- ^ Paul Hayes, Modern British Foreign Policy: The nineteenth century, 1814–80 (1975) pp. 155–73.

- ^ Douglas Dakin, Greek Struggle for Independence: 1821–1833 (U of California Press, 1973).

- ^ Charles Jelavich and Barbara Jelavich, The establishment of the Balkan national states, 1804-1920 (1977) pp 76-83.

- ^ R. W. Seton-Watson, Britain in Europe 1789-1914, a Survey of Foreign Policy (1937) pp. 301-60.

- ^ Orlando Figes, The Crimean War: A History (2011).

- ^ Seton-Watson, Britain in Europe 1789-1914, 319-327.

- ^ Nicholas Riasanovsky, Nicholas I and official nationality in Russia 1825-1855 (1969) pp 250-52, 263-66.

- ^ Robert Pearce, "The results of the Crimean War." History Review 70 (2011): 27-33.

- ^ Figes, The Crimean War, 68-70, 116-22, 145-150.

- ^ Figes, The Crimean War, 469-71.

- ^ Elie Halevy and R.B. McCallum, Victorian years: 1841-1895 (1951) p 426.

- ^ Donald Malcolm Reid, "The 'Urabi revolution and the British conquest, 1879–1882", in M.W. Daly, ed., The Cambridge History of Egypt, vol. 2: Modern Egypt, from 1517 to the end of the twentieth century (1998) pp. 217=238.

- ^ Richard Shannon, Gladstone (1999) 2: 298–307

- ^ H.C.G. Matthew, Gladstone 1809-1898 (1997) pp 382-94.

- ^ Afaf Lutfi Al-Sayyid, Egypt and Cromer: A Study in Anglo-Egyptian Relations (1969) pp 54–67.

- ^ Roger Owen, Lord Cromer: Victorian Imperialist, Edwardian Proconsul (Oxford UP, 2005).

- ^ He adds, "All the rest were manoeuvres which left the combatants at the close of the day exactly where they had started. A.J.P. Taylor, "International Relations" in F.H. Hinsley, ed., The New Cambridge Modern History: XI: Material Progress and World-Wide Problems, 1870–98 (1962): 554.

- ^ Taylor, "International Relations" p. 554

- ^ Peter J. Cain and Anthony G. Hopkins, "Gentlemanly capitalism and British expansion overseas II: new imperialism, 1850–1945." Economic History Review 40.1 (1987): 1–26. online

- ^ a b c d Hopkins, A. G. (July 1986). "The Victorians and Africa: A Reconsideration of the Occupation of Egypt, 1882". The Journal of African History. 27 (2): 363–391. doi:10.1017/S0021853700036719. JSTOR 181140. S2CID 162732269.

- ^ Dan Halvorson, "Prestige, prudence and public opinion in the 1882 British occupation of Egypt." Australian Journal of Politics & History 56.3 (2010): 423-440.

- ^ John S. Galbraith and Afaf Lutfi al-Sayyid-Marsot, "The British occupation of Egypt: another view." International Journal of Middle East Studies 9.4 (1978): 471–488.

- ^ Tombs, Robert The English and their History

- ^ A History of Egypt

- ^ Charlie Laderman, Sharing the Burden: The Armenian Question, Humanitarian Intervention, and Anglo-American Visions of Global Order (Oxford University Press, 2019).

- ^ Matthew P. Fitzpatrick, "‘Ideal and Ornamental Endeavours’: The Armenian Reforms and Germany's Response to Britain's Imperial Humanitarianism in the Ottoman Empire, 1878–83." Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 40.2 (2012): 183-206.

- ^ Robert John Alston and Stuart Laing, Unshook Till the End of Time: A History of Relations Between Britain & Oman 1650 - 1970 (2017).

- ^ John M. MacKenzie, “The Sultanate of Oman,” History Today (1984) 34#9 pp 34-39

- ^ J. C. Hurewitz, " Britain and the Middle East up to 1914,” in Reeva S. Simon et al., eds., Encyclopedia of the Modern Middle East (1996) 1: 399-410

- ^ Anthony Sampson, Seven sisters: The great oil companies and the world they shaped (1975) pp 52-70.

- ^ Daniel Yergin, The Prize: The epic quest for oil, money and power (1991) pp 135-64.

- ^ Kenneth J. Panton, Historical Dictionary of the British Empire (2015) pp 19-21.

- ^ Spencer Mawby, "Workers in the Vanguard: the 1960 industrial relations ordinance and the struggle for independence in Aden." Labor History 57.1 (2016): 35-52 online.

- ^ Spencer Mawby, "Orientalism and the failure of British policy in the Middle East: The case of Aden." History 95.319 (2010): 332-353. online

- ^ James E Olson and Robert Shadle, eds., Historical dictionary of the British Empire (1996) 2:9-11.

- ^ Peter Hinchcliffe et al. Without Glory in Arabia: The British Retreat from Aden (2006).

- ^ Spencer Mawby, "Orientalism and the failure of British policy in the Middle East: The case of Aden." History 95.319 (2010): 332-353.

- ^ Eugene Rogan, The Fall of the Ottomans: The Great War in the Middle East (2015) excerpt and online summary.

- ^ Olusoga, David The World's War

- ^ M.S. Anderson, The Eastern question, 1774-1923: A study in international relations (1966) pp 310–52.

- ^ Paul C. Helmreich, From Paris to Sèvres: The Partition of the Ottoman Empire at the Peace Conference of 1919–1920 (Ohio University Press, 1974) ISBN 0-8142-0170-9

- ^ Fromkin, A Peace to End All Peace (1989), pp. 49–50.

- ^ Roderic H. Davison; Review "From Paris to Sèvres: The Partition of the Ottoman Empire at the Peace Conference of 1919–1920" by Paul C. Helmreich in Slavic Review, Vol. 34, No. 1 (Mar. 1975), pp. 186–187

- ^ Timothy J. Paris, "British Middle East Policy-Making after the First World War: The Lawrentian and Wilsonian Schools." Historical Journal 41.3 (1998): 773–793 online.

- ^ Timothy J. Paris,Britain, the Hashemites and Arab rule: the sherifian solution (Routledge, 2004).

- ^ Robert McNamara, The Hashemites: the dream of Arabia (2010).

- ^ Peter Sluglett, Britain in Iraq: contriving king and country, 1914-1932 (Columbia University Press, 2007).

- ^ Abbas Kadhim, Reclaiming Iraq: the 1920 revolution and the founding of the modern state (U of Texas Press, 2012).

- ^ Charles Tripp, A History of Iraq (3rd ed. 22007) pp 50–57.

- ^ Segev, Tom, One Palestine, Complete

- ^ Segev, Tom One Palestine

- ^ Hyamson, Albert Montefiore. Palestine: A Policy Methuen, 1942, p. 147

- ^ John Broich, Blood, Oil and the Axis: The Allied Resistance Against a Fascist State in Iraq and the Levant, 1941 (Abrams, 2019).

- ^ Ashley Jackson, The British Empire and the Second World War (2006) pp 145–54.

- ^ Robert Lyman, Iraq 1941: The Battles for Basra, Habbaniya, Fallujah and Baghdad (Osprey Publishing, 2006).

- ^ Stefanie K. Wichhart, "Selling Democracy During the Second British Occupation of Iraq, 1941–5." Journal of Contemporary History 48.3 (2013): 509–536.

- ^ Daniel Silverfarb, The twilight of British ascendancy in the Middle East: a case study of Iraq, 1941-1950 (1994). pp 1–7.

- ^ "Ceremonies: State visits". Official web site of the British Monarchy. Archived from the original on 2008-11-06. Retrieved 2008-11-29.

- ^ John Franzén, "Development vs. reform: attempts at modernisation during the twilight of British influence in Iraq, 1946–58." Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 37.1 (2009): 77–98.

- ^ Sylvia Ellis (2009). Historical Dictionary of Anglo-American Relations. Scarecrow Press. p. 212. ISBN 9780810862975.

- ^ Peden, G. C. (December 2012), "Suez and Britain's Decline as a World Power", The Historical Journal, 55 (4): 1073–1096, doi:10.1017/S0018246X12000246, S2CID 162845802

- ^ Simon C. Smith, ed. Reassessing Suez 1956: New perspectives on the crisis and its aftermath (Routledge, 2016).

- ^ David M. McCourt, "What was Britain's 'East of Suez role'? Reassessing the withdrawal, 1964–1968." Diplomacy & Statecraft 20.3 (2009): 453–472.

- ^ Hessameddin Vaez-Zadeh, and Reza Javadi, "Reassessing Britain's Withdrawal from the Persian Gulf in 1971 and its Military Return in 2014." World Sociopolitical Studies 3.1 (2019): 1–44 Online.

- ^ David Sanders and David Houghton, Losing an empire, finding a role: British foreign policy since 1945 (2017) pp 118–31.

Further reading

[edit]- Agoston, Gabor, and Bruce Masters. Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire (2008)

- Anderson, M.S. The Eastern Question, 1774-1923: A Study in International Relations (1966) online, the major scholarly study.

- Barr, James. "A Line in the Sand: British-French Rivalry in the Middle East 1915–1948." Asian Affairs 43.2 (2012): 237–252.

- Brenchley, Frank. Britain and the Middle East: Economic History, 1945-87 (1991).

- Bullard, Reader. Britain and the Middle East from Earliest Times to 1963 (3rd ed. 1963)

- Cleveland, William L., and Martin Bunton. A History Of The Modern Middle East (6th ed. 2018 4th ed. online

- Corbett, Julian Stafford. England in the Mediterranean; a study of the rise and influence of British power within the Straits, 1603-1713 (1904) online

- D'Angelo, Michela. "In the 'English' Mediterranean (1511–1815)." Journal of Mediterranean Studies 12.2 (2002): 271–285.

- Deringil, Selim. "The Ottoman Response to the Egyptian Crisis of 1881-82" Middle Eastern Studies (1988) 24#1 pp. 3-24 online

- Dietz, Peter. The British in the Mediterranean (Potomac Books Inc, 1994).

- Fieldhouse, D. K. Western Imperialism in the Middle East 1914-1958 (Oxford UP, 2006)

- Harrison, Robert. Britain in the Middle East: 1619-1971 (2016) short scholarly narrative excerpt

- Hattendorf, John B., ed. Naval Strategy and Power in the Mediterranean: Past, Present and Future (Routledge, 2013).

- Holland, Robert. "Cyprus and Malta: two colonial experiences." Journal of Mediterranean Studies 23.1 (2014): 9–20.

- Holland, Robert. Blue-water empire: the British in the Mediterranean since 1800 (Penguin UK, 2012). excerpt

- Laqueur, Walter. The Struggle for the Middle East: The Soviet Union and the Middle East 1958-70 (1972) online

- Louis, William Roger. The British Empire in the Middle East, 1945–1951: Arab Nationalism, the United States, and Postwar Imperialism (1984)

- MacArthur-Seal, Daniel-Joseph. "Turkey and Britain: from enemies to allies, 1914–1939." Middle Eastern Studies (2018): 737-743.

- Mahajan, Sneh. British Foreign Policy 1874-1914: The Role of India (2002).

- Anderson, M.S. The Eastern Question, 1774-1923: A Study in International Relations (1966) online, the major scholarly study.

- Marriott, J. A. R. The Eastern Question An Historical Study In European Diplomacy (1940), Older comprehensive study; more up-to-date is Anderson (1966) Online

- Millman, Richard. Britain and the Eastern Question, 1875–1878 (1979)

- Monroe, Elizabeth. Britain's moment in the Middle East, 1914-1956 (1964) online

- Olson, James E. and Robert Shadle, eds., Historical dictionary of the British Empire (1996)

- Owen, Roger. Lord Cromer: Victorian Imperialist, Edwardian Proconsul (Oxford UP, 2005) Online review, On Egypt 1882-1907.

- Pack, S.W.C Sea Power in the Mediterranean – has a complete list of fleet commanders

- Panton, Kenneth J. Historical Dictionary of the British Empire (2015).

- Schumacher, Leslie Rogne. "A 'Lasting Solution': the Eastern Question and British Imperialism, 1875-1878." (2012). online; Detailed bibliography

- Seton-Watson, R. W. Disraeli, Gladstone, and the Eastern question; a study in diplomacy and party politics (1972) Online

- Seton-Watson, R. W. Britain in Europe 1789-1914, a Survey of Foreign Policy (1937) Online

- Smith, Simon C. Ending Empire in the Middle East: Britain, the United States and Post-war Decolonization, 1945-1973 (2012).

- Smith, Simon C. Britain's Revival and Fall in the Gulf: Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, and the Trucial States, 1950-71 (2004)

- Smith, Simon C. Britain and the Arab Gulf after Empire: Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates, 1971-1981 (Routledge, 2019).

- Steele, David. "Three British Prime Ministers and the Survival of the Ottoman Empire, 1855–1902." Middle Eastern Studies 50.1 (2014): 43-60, On Palmerston, Gladstone and Salisbury.

- Syrett, David. "A Study of Peacetime Operations: The Royal Navy in the Mediterranean, 1752–5." The Mariner's Mirror 90.1 (2004): 42-50.

- Talbot, Michael. British-Ottoman Relations, 1661-1807: Commerce and Diplomatic Practice in Eighteenth-Century Istanbul (Boydell & Brewer, 2017).

- Thomas, Martin, and Richard Toye. "Arguing about intervention: a comparison of British and French rhetoric surrounding the 1882 and 1956 invasions of Egypt." Historical Journal 58.4 (2015): 1081-1113 online.

- Tuchman, Barbara W. Bible and Sword: England and Palestine from the Bronze Age to Balfour (1982), popular history of Britain in the Middle East; online

- Uyar, Mesut, and Edward J. Erickson. A Military History of the Ottomans: From Osman to Atatürk (ABC-CLIO, 2009).

- Venn, Fiona. "The wartime ‘special relationship’? From oil war to Anglo-American Oil Agreement, 1939–1945." Journal of Transatlantic Studies 10.2 (2012): 119-133.

- Williams, Kenneth. Britain And The Mediterranean (1940) online free

- Yenen, Alp. "Elusive forces in illusive eyes: British officialdom's perception of the Anatolian resistance movement." Middle Eastern Studies 54.5 (2018): 788-810. online[dead link]

- Yergin, Daniel. The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and Power (1991)

Historiography

[edit]- Ansari, K. Humayun. "The Muslim world in British historical imaginations: ‘re-thinking Orientalism’?." Orientalism Revisited (Routledge, 2012) pp. 29-58.

- Macfie, A.L. The Eastern Question 1774-1923 (2nd ed. Routledge, 2014).

- Tusan, Michelle. “Britain and the Middle East: New Historical Perspectives on the Eastern Question.” History Compass 8#3 (2010): 212–222.

Primary sources

[edit]- Anderson, M.S. ed. The great powers and the Near East, 1774-1923 (Edward Arnold, 1970).

- Bourne, Kenneth, ed. The Foreign Policy of Victorian England 1830-1902 (1970); 147 primary documents, plus 194 page introduction. online free to borrow

- Fraser, T. G. ed. The Middle East, 1914-1979 (1980) 102 primary sources; focus on Palestine/Israel

- Hurewitz, J. C. ed. The Middle East and North Africa in world politics: A documentary record vol 1: European expansion: 1535-1914 (1975); vol 2: A Documentary Record 1914-1956 (1956)vol 2 online